Blessed

A wakeup call.

In November of last year, I accompanied my dad as he buried his father. Ten days earlier, I was walking the halls of the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City’s Historic Center. I had long been aware of the centuries-old structure, but hadn’t gotten a chance to experience it in person until October’s Noche de Museos, a city-wide initiative that sees dozens of museums and cultural institutions stay open beyond regular hours on every final Wednesday of the month (excluding January). Each museo often hosts free events or activities—including choir performances and arts and crafts—followed by a guided tour. Eager to check out one of the city’s most impressive and artistically important buildings, I began to walk its storied halls before the Día de Muertos-inspired theatrical presentation had finished.

Some of the museum’s staircases were closed off due to renovations, but murals by some of Mexico’s most iconic artists—Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros—were still visible along and above stairs despite scaffolding. Even at a distance, pieces like Cortés y La Malinche (1926) by José Clemente Orozco are impressive.

While walking on one of San Ildefonso’s upper levels, I came across Los aristócratas (1923-24), another fresco by Orozco. Attention-grabbing in its own right, the work of art reminded me of a particular scene in the 2002 film Amar te Duele. Your classic “rich-poor forbidden love story,” the indie movie does a great job of capturing Mexico’s capital near the turn-of-the-century, and the raw, creative boom of the moment. (Also check out Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores perros from two years earlier for another authentic slice of the city.)

It’s always a treat interacting with things I’ve seen online in real life; I recently did just this with a taquería and cantina featured in a Vice video I initially watched almost a decade ago.

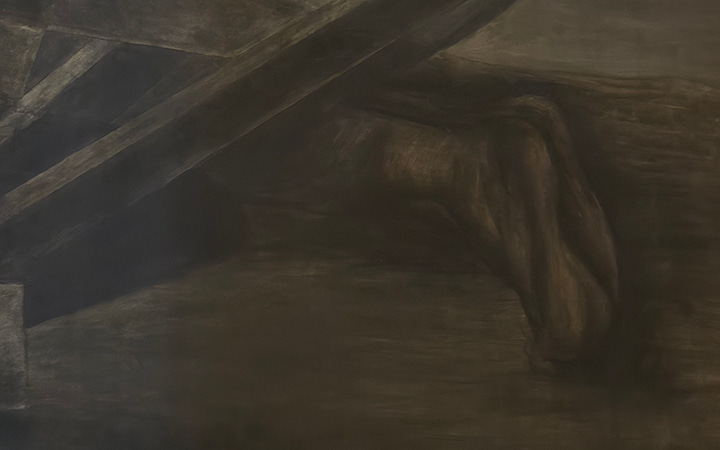

There’s a certain section of the old college that features a series of murals inspired by the Mexican Revolution of the early 1900s. Many of the artwork painted directly onto the museum’s walls include dark colors by choice; some have had their bold reds and blues fade over time.

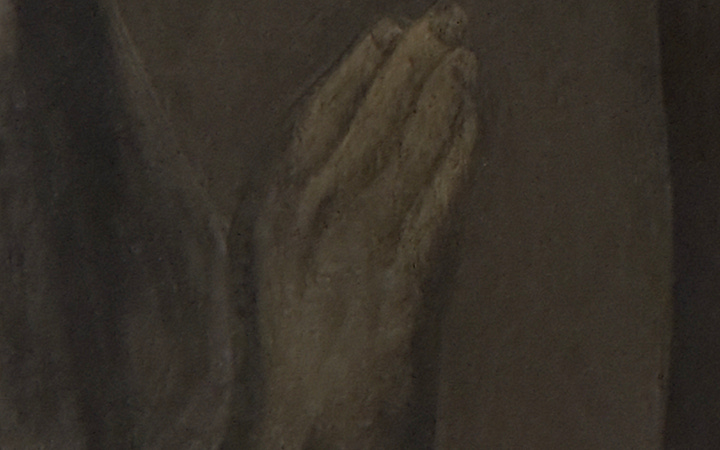

One fresco that made me pause longer than the others depicts two muted, solemn figures facing each other while between an archway and field equipment. Titled La bendición (1926) and painted by Orozco, the 99-year-old work of art captures a scene and concept that are relevant today: a parent’s blessing of their child.

For as long as I can remember, my mother has been giving me her blessing before I step outside the house; go for a job interview; walk through airport security; and hang up the phone. Her parents, godparents, and important aunts and uncles did the same for her, but most of these people are no longer around.

I can’t recall if my father’s father did the same for him, but if he did, he no longer can.

Death isn’t something I’ve had too much close experience with, but the fear of it is something I know all too well.

Why, then, have I led a life of negligence and carelessness? Why is it that I wallow in action-less analysis when I encounter images like La bendición instead of calling my parents more frequently? My siblings? My friends?

Time after time, I’m faced with the reality that I’m too comfortable in remissness. I never carry this out with bad intentions or pompous expectations that the world will always be there when I’m ready because it has to be, but realize it’s the impression I likely give off.

The truth of the matter is that I’m undeniably blessed. Even in the face of unemployment, health scares, homesickness, and other obstacles, I recognize the magic that had to happen to be able to exist to go through these things. Additionally, I recognize that I’m never alone—I’m accompanied by every time a loved one or stranger has thought of me, whether I’ve known of it or not.

I know I risk reading like an idealist, but I’m truly of the belief—and serve as testament—that things stick around. I’m blessed to have encountered certain people at specific moments, even if they’ve been carried away by time.

Orozco’s fresco strikes me from a number of angles. Firstly, it gives me the opportunity to imagine myself in the faceless man’s kneeling position. Secondly, it reminds me of the ever-present uncertainty surrounding everything from the mundane to the monumental. Lastly, La bendición preoccupies me with the notion of faith, and willingness of countless nameless people to fight and sacrifice in the name of a greater good.

Blessings might not mean something to everyone, but they mean everything to those who believe in them. When I was at my lowest, I asked several peers to pray for me in hopes that they could help me achieve what I couldn’t for myself. I can’t say with certainty that their hopes for me were received and acted upon by some higher deity, but I felt them at my core and used them to keep going, if even for only a moment.

I often, randomly, think about Kendrick Lamar’s lyrics on the songs “ELEMENT.” and “FEEL.” from his 2017 album DAMN, specifically ones in which he shares that nobody is praying for him.

My mother still prays for me and it saddens me to know that the day will come when she no longer does because she no longer can. While I still have her, I must cherish her in a manner that leaves no doubt that I know how blessed I’ve been. I strive to follow my father’s example with his dad and do what I can while I can to avoid living with regret.